Back in January I participated in a panel on Math Games over at the Global Math. I meant to write this follow-up post shortly after, but January was a hell of a month for me and it slipped to the wayside. See my talk here, at the 2:55 mark.

I sorta hit the same point over and over, using six different games as examples, but that’s because I truly believe it is the most important point in both designing math games as well as choosing which games to use in your classroom. If the math action required is separate from the game action performed, then it will seem forced and lead students to believe that math is useless.

This can be fine if you want. Maybe you want to play a trivia game, where the knowledge action is separate from the game action. But if you pretend that they are the same, then you have problems.

This can be fine if you want. Maybe you want to play a trivia game, where the knowledge action is separate from the game action. But if you pretend that they are the same, then you have problems.

This is the same essential argument as the one against psuedocontext. It may seem like you could say “It’s just a game,” but students see it as a shallow way to spice something up that can’t stand on its own. (I’m not saying review games and trivia games don’t have their place, but they can’t expand beyond their place.)

Below are the six examples I gave, with the breakdown of their game action and math action. I hope to use what I learned in this process to have us make a new, better math game in the summer, during Twitter Math Camp.

A Pac-Man game where you can only eat a certain ghost, depending on the solution to an equation.

If we apply the metric above and think about what is the math action and what is the game action? Here, the math actions are simplifying expressions and adding/subtracting, but the game actions are navigating the maze and avoiding ghosts. If I’m a student playing this game, I want to play Pac-Man. The math here is preventing me from playing the game, not aiding me, which makes me resentful towards that math.

Verdict: Bad

In this game, you help penguins cross a shark filled expanse by placing a platform for them to bounce over. Because of a time limit, you can’t calculate precisely where the platform needs to go, so you need to estimate. That skill is both the math action and the game action, so that alignment means that this game accomplishes its goal.

In this game, you help penguins cross a shark filled expanse by placing a platform for them to bounce over. Because of a time limit, you can’t calculate precisely where the platform needs to go, so you need to estimate. That skill is both the math action and the game action, so that alignment means that this game accomplishes its goal.

Verdict: Good

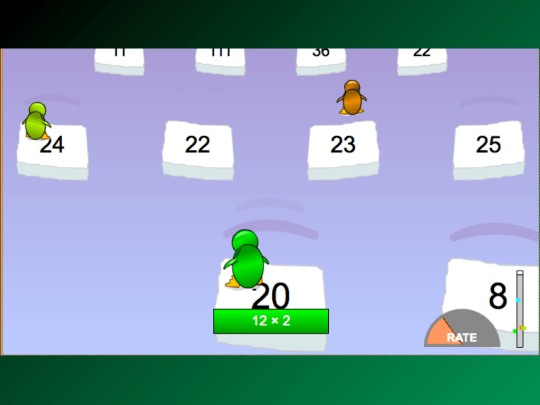

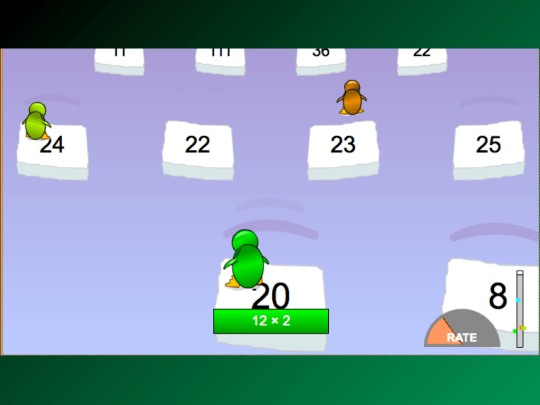

Here you pick a penguin, color them, and then race other people online jumping from iceberg to iceberg. The problem is that the math action is multiplying, which is not at all the same. The game gets worse, though, because AS the multiplying is preventing you from getting to the next iceberg, because maybe you are not good at it yet, you visibly see the other players pulling ahead, solidifying in your mind that you are bad at math, at exactly the point when you need the most support. A good math game should be easing you into the learning, not penalizing you when you are at your most vulnerable point, the beginning of your learning.

Here you pick a penguin, color them, and then race other people online jumping from iceberg to iceberg. The problem is that the math action is multiplying, which is not at all the same. The game gets worse, though, because AS the multiplying is preventing you from getting to the next iceberg, because maybe you are not good at it yet, you visibly see the other players pulling ahead, solidifying in your mind that you are bad at math, at exactly the point when you need the most support. A good math game should be easing you into the learning, not penalizing you when you are at your most vulnerable point, the beginning of your learning.

Verdict: Terrible

This is a game that seems like it has potential: given a number, factor that number into a rectangle (shout-out to Fawn Nguyen here in my talk), then drop the block you created by factoring to play Tetris.

Again, the math action is factoring whole numbers and creating visual representations, which are good actions. But the game action is dropping blocks into a space to fill up lines. As Megan called it, though, we have a carrot and stick layout here, and often in many games. Do the math, and you get to play a game afterwards. (Also, the Tetris part doesn’t really pan out, because all the blocks are rectangles, which is the most boring game of Tetris ever.)

Verdict: Bad

I’ve written about Dragonbox before, so I won’t write about it too much here. The goal of Dragonbox is to isolate the Dragon Box by removing extraneous monsters and cards. The math actions include combining inverses to zero-out or one-out, or to isolate variables. The game action is to combine day/night cards to swirl them out, or isolate the dragon box. The game action is in perfect alignment with the math action, which makes the game very engaging and very instructive.

Verdict: Good

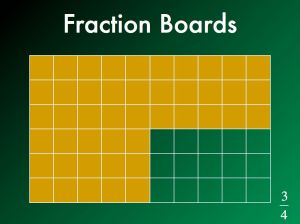

The board game I created last year (and you can also make your own free following instructions here, or buy at the above link). In this game, the game actions were designed to match up with math actions. Simplifying a radical by moving a root outside the radical sign, as in the picture above, is done by playing the root card outside and removing the square from the inside (and keeping it as points). You also need to identify when a radical is fully simplified, which you do in game actions by slapping the board (because everything is better with slapping) and keeping the cards there as points.

You also need to identify when a radical is fully simplified, which you do in game actions by slapping the board (because everything is better with slapping) and keeping the cards there as points.

Verdict: Good

Final Note

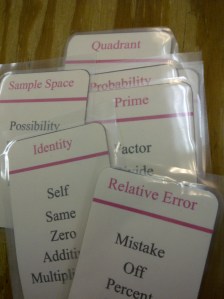

One of the real challenges of finding good math games, as a teacher, is curriculum. Most math teachers know of several good math games, like Set or Blokus. While these games are great and very mathematical, they’re not the math content that we usually need to teach in our classes. So the challenge falls on us to create our own games, but making good math games is hard. (Making bad ones is pretty easy.) On that note, if you know of some good math games (that meet the criteria mentioned in this post), drop a line in the comments!