Anagrams and Quads

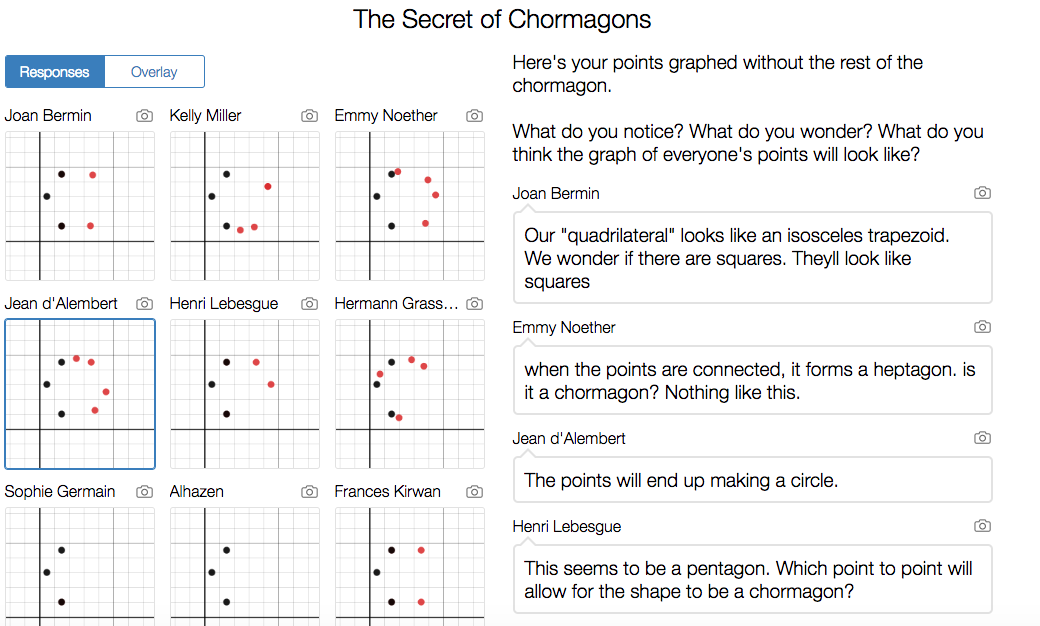

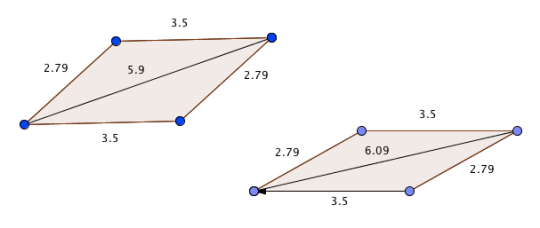

In geometry we’re learning about the correspondence of congruence statements (i.e. ∆ABC ≅ ∆DEF means that A maps to D, BC = EF, angle CAB ≅ angle FDE, etc). One fun type of problem you can do with this is a self-referential congruence statement to highlight symmetry. For example, if LIMA ≅ MALI, what type of quadrilateral is it?

So the first question I had was “How many of these types of problems can you have?” The answer is not just the same as how many ways there are to arrange 4 letters (4!), because you still need to connect the four points in the same order (although you can change whether you go clockwise or counterclockwise). So if our starting ordering is 1234, you can have the following orderings:

| 1234 | Identity | OPTS |

| 2143 | Isosceles Trapezoid | POST |

| 2341 | Square | PTSO |

| 3412 | Parallelogram | TSOP |

| 4123 | Square | SOPT |

| 1432 | Kite | OSTP |

| 4321 | Isosceles Trapezoid | STPO |

| 3214 | Kite | TPOS |

(As a side note, how do you solve these problems? You can list out all the sub-congruencies and mark up a diagram. But I like to think of the mapping of points and determine what transformation that would be. For example, with OPTS to POST, P and O switch places, and S and T switch places, so it must be a reflection with the line of reflection down the middle of lines PO and ST. This makes an isosceles trapezoid.)

I picked OPTS as a starting point because it’s the four-letter work with the most anagrams (OPTS, STOP, SPOT, POST, POTS) so I figured some would should up in this work and was surprised there was only one. But then I realized that which one I start with matters: if I start with OPTS, only POST is a valid shape, but if I start with STOP, then SPOT and POTS are valid.

So then I went through a list of four letter anagrams to find more that fit the patterns I need above. Below is a non-comprehensive list you can use for these types of problems if you, like me, like using words instead of just ABCD.

| 2143 | MANE | AMEN |

| 2143 | ACTS | CAST |

| 2143 | TIME | ITEM |

| 2143 | SURE | USER |

| 2341 | EMIT | MITE |

| 2341 | MITE | ITEM |

| 2341 | EACH | ACHE |

| 2341 | ABET | BETA |

| 3412 | MALI | LIMA |

| 3412 | EMIT | ITEM |

| 3412 | ARTS | TSAR |

| 3412 | REPO | PORE |

| 3412 | CODE | DECO |

| 3412 | DEMO | MODE |

| 3412 | GOER | ERGO |

| 4123 | ALES | SALE |

| 4123 | LOTS | SLOT |

| 4123 | OPEN | NOPE |

| 1432 | BETA | BATE |

| 1432 | DEMO | DOME |

| 1432 | MATE | META |

| 1432 | GORY | GYRO |

| 4321 | ABUT | TUBA |

| 4321 | TIME | EMIT |

| 4321 | RATS | STAR |

| 4321 | BARD | DRAB |

| 3214 | AGED | EGAD |

| 3214 | TIME | MITE |

| 3214 | RATS | TARS |

| 3214 | MANE | NAME |

If you have more anagram suggestions, leave them in the comments!